Zionism, a movement advocating for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, emerged in the late 19th century against a backdrop of rising nationalism and pervasive anti-semitism in Europe. This period was marked by significant socio-political changes, including the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of the nationalist movements. Anti-Jewish sentiment was particularly acute in Eastern Europe, serving as a catalyst for the Zionist movement.

In this series, I will explore the history of Zionism and its intricate relationship with Judaism, delving into the various ideological strands, significant events, and key figures that have shaped this movement. Through a comprehensive examination, we will uncover the complexities and debates that continue to influence the Jewish and global communities today.

The Dreyfus Affair and Its Impact

A pivotal event in this context was the Dreyfus Affair in France (1894), which galvanized the Zionist cause. Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French Army, was accused of treason for allegedly passing military secrets to Germany. His conviction was the result of a highly publicized trial that many viewed as tainted by anti-Semitism. Military officials and politicians posited that Dreyfus was more loyal to the Zionist cause than to France, suggesting he was part of a broader Jewish conspiracy to undermine the nation.

The primary evidence against him was a document known as the “bordereau,” a handwritten note outlining military secrets purportedly passed to a German military attaché. The prosecution relied on expert testimonies asserting that the handwriting matched Dreyfus’s, leading to his conviction and life sentence on Devil’s Island. The trial drew public criticism from notable Zionist figures such as Theodor Herzl, David Ben-Gurion, and Chaim Weizmann, who used it to rally support for the movement.

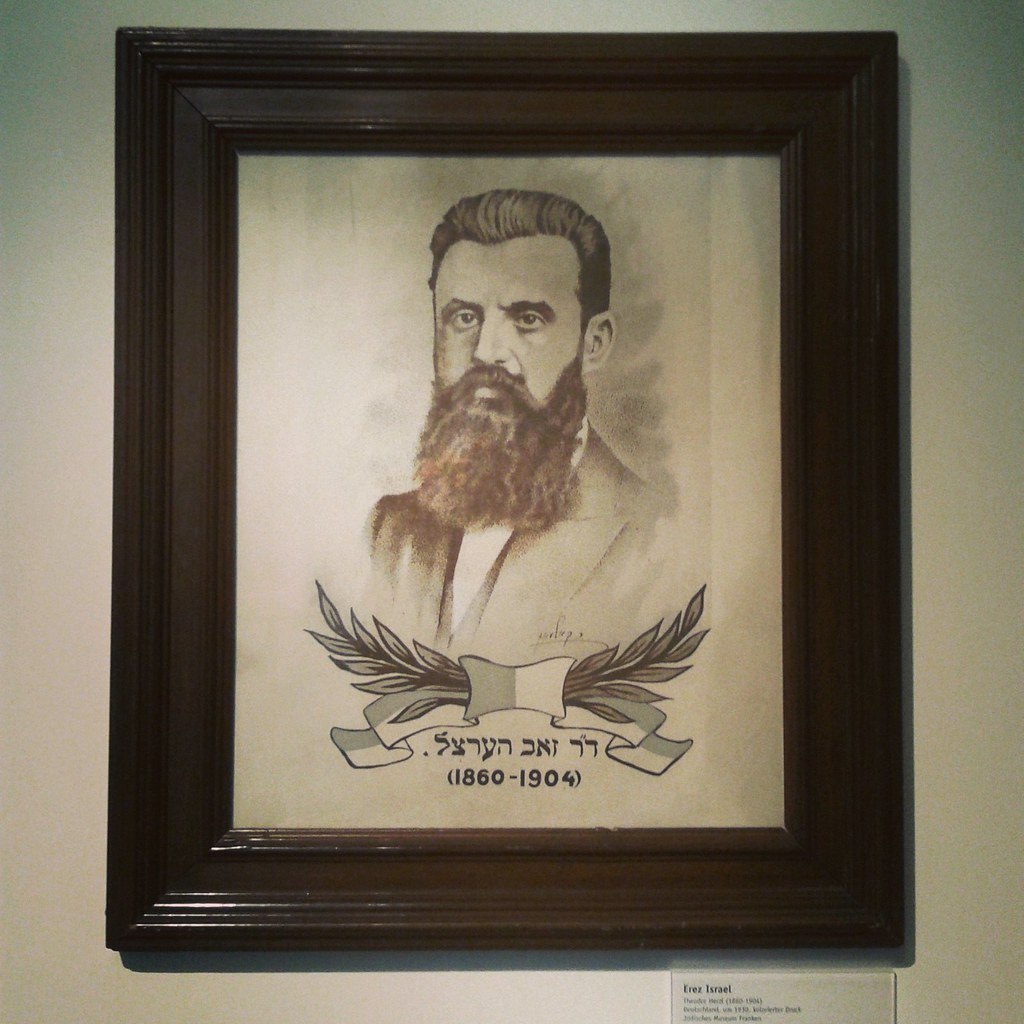

Theodor Herzl and Political Zionism

Theodor Herzl, often regarded as the father of modern political Zionism, was a Jewish journalist and playwright born in 1860 in Budapest, Hungary. His seminal work, Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), published in 1896, argued for the establishment of a sovereign Jewish state as a solution to widespread anti-Semitism in Europe. Herzl envisioned a political movement that sought international recognition and support for Jewish self-determination, culminating in the First Zionist Congress in 1897 in Basel, Switzerland, where he famously declared, “If you will it, it is no dream.” Herzl’s determination to establish a Jewish state was so strong that he believed achieving this goal was paramount, even if it meant marginalizing or sacrificing certain segments of the Jewish population that he perceived as inferior or less supportive of the Zionist cause.

Political Zionism, primarily articulated by Herzl, centered on the urgent need for a sovereign Jewish state as a refuge from anti-Semitism and persecution. Herzl and his followers believed that political action, including diplomacy and negotiations with world powers, was essential to secure the rights and safety of Jews globally. This strand emphasized establishing institutions, such as the Jewish National Fund, to facilitate land purchases in Palestine and create a political framework that would support Jewish immigration and governance. Herzl’s pragmatic approach to establishing a separate Jewish state often conflicted with traditional Judaic values, as it involved seeking support from imperial powers, raising ethical concerns about collaborating with colonial regimes.

This was evident with the Ha’avara Agreement, a controversial pact made in 1933 between the Nazi regime and Zionist German Jews, allowing Jewish emigrants to transfer a portion of their assets to Palestine in the form of German goods. This agreement, while facilitating Jewish immigration to Palestine, also sparked significant debate and criticism for seemingly collaborating with a regime that was persecuting Jews.

Cultural and Religious Zionism

Cultural Zionism, championed by thinkers like Ahad Ha’am, shifted the focus from mere political statehood to the revival of Jewish culture and identity. This perspective held that a vibrant Jewish culture, expressed through the Hebrew language, arts, and education, was fundamental to the survival of the Jewish people. Cultural Zionists argued that establishing a Jewish homeland should not only be about political autonomy but also about creating a rich cultural life that could rejuvenate Jewish identity and foster a sense of community among Jews worldwide.

Religious Zionism drew from biblical texts and religious teachings to justify the Jewish return to the land of Israel. Proponents of this ideology, including figures like Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, viewed the establishment of Israel as a fulfillment of biblical prophecies regarding the Jewish people’s return to their ancestral homeland. They believed that the land of Israel was not only a physical territory but also a divinely ordained promise. Religious Zionists often see the modern state of Israel as a precursor to the Messianic age, wherein the fulfillment of biblical prophecies would lead to peace and spiritual renewal for the Jewish people and the world at large.

Critiques and Opposition

However, not all Jews supported Zionism. Some Orthodox Jews argued that the establishment of a Jewish state should be divinely ordained, asserting that Jewish redemption could only come through the Messiah. Groups like Neturei Karta vehemently opposed Zionism, viewing it as a rebellion against God’s will. They believed that human efforts to create a Jewish state contradicted the traditional Jewish teachings that redemption and the return to the Holy Land must be accomplished through divine intervention. As a result, these groups are often attacked and vilified for their stance, and are sometimes labeled as antisemitic by Zionist supporters. The irony lies in the fact that they, as devout Jews, are labeled antisemitic for holding onto their traditional beliefs and religious convictions

Prominent Jewish figures such as Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud expressed skepticism about nationalism, arguing that Jewish identity should not be tied to a specific territory and that assimilation and integration into wider European societies were preferable. This stance was rooted in the Judaic value of “galut” (exile), which emphasized the spiritual and religious significance of living in the diaspora.

Leftist Jewish movements, particularly those aligned with socialism, critiqued Zionism for its nationalist tendencies, believing that it diverted attention from class struggle and advocating for internationalism, viewing the fight against capitalism and anti-Semitism as interconnected. These critics argued that Zionism’s focus on creating a national state ran counter to the universalist principles of justice and equality that are also central to Jewish ethics. They, too, faced attacks and vilification for their opposition to Zionism.

Arab Nationalism and International Responses

As Zionism gained traction, it increasingly came into conflict with Arab nationalism. Arab residents of Palestine were deeply concerned about the implications of a Jewish state, fearing dispossession and marginalization. The influx of Jewish immigrants was perceived as a threat to their land, culture, and social fabric. Arab nationalists argued that Palestine was an integral part of the Arab world and resented the notion of a Jewish state within it. The rise of Arab nationalism in the early 20th century was, in part, a response to the growing Zionist movement. Leaders like Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, mobilized opposition to Zionism, organizing protests and lobbying against Jewish immigration and land purchases. This resistance laid the groundwork for future conflicts.

Zionism also elicited varied responses from international communities. Some European governments, particularly during World War I, viewed Zionism as a way to gain Jewish support against the Ottomans. The Balfour Declaration of 1917, issued by the British government, expressed support for a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, igniting further debate and contention. In the context of anti-colonial struggles, some critics viewed Zionism as a form of colonialism, arguing that it mirrored European colonial endeavors by imposing a settler society over an indigenous population.

The Dangers of Conflating Zionism with Judaism

It is crucial to recognize that Judaism is not a monolith, and conflating Zionism with Judaism can have dangerous implications. While Zionism is a political movement advocating for the establishment of a Jewish homeland, Judaism is a diverse and ancient religion with various interpretations and beliefs.

During World War II, the conflation of Zionism and Judaism had severe consequences. The Nazi regime used propaganda to portray Jews as a monolithic group with a single political agenda, leading to widespread anti-Semitic persecution. This dangerous narrative contributed to the horrors of the Holocaust, where millions of Jews were systematically exterminated.

For example, the Nazi propaganda often depicted all Jews as being part of a global Zionist conspiracy, which was used to justify their persecution. This false narrative ignored the diverse experiences and beliefs within the Jewish community, including those who opposed Zionism for religious or ideological reasons.

Conclusion

The Zionist movement, born out of a desire to create a safe haven for Jews amid rising anti-Semitism, has grown into a multifaceted and deeply influential force in global politics. While it succeeded in establishing the State of Israel and provided refuge for countless Jews, it also ignited complex and enduring conflicts with Arab populations in Palestine and raised ethical questions about nationalism, colonialism, and the true nature of Jewish identity.

The rich diversity within Judaism itself, with varying stances on Zionism, underscores the importance of recognizing the distinction between religious and political identities. The historical conflation of Zionism with Judaism has often led to dangerous oversimplifications, contributing to persecution and misunderstanding. Acknowledging the breadth of Jewish thought and the legitimate critiques of Zionism is essential in fostering a more nuanced and compassionate dialogue.