The Hungarian Refugee Crisis of 1956 seemed like nothing short of a miracle. Countries around the world stepped in to help the Hungarians, but now refugees are demonized and detained; society has taken a sharp turn towards anti-immigrant rhetoric. My first book, Young Men Go West, is about the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and my grandfather’s solo journey as a 16-year-old refugee to the United States.

As the Hungarian Revolution was crushed in November 1956, tens of thousands fled across the border, braving the winter on foot to escape Soviet repression. Within 48 hours, aid and volunteers arrived in Austria where the majority of refugees went, and relocation efforts swiftly began. Despite initial chaos, Austrians, Yugoslavs, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) organized an effective response.

It was the first refugee crisis that the world witnessed in real time. Photos and footage of the refugees trudging through the snow were shown to the world in magazines, newspapers, TV, cinema reels, and announced on the radio. Although people in the west were not aware of the important events leading up to the Hungarian Revolution, they felt solidarity with the resistance, and many wanted to help. Elvis Presley even urged his fans to contribute, helping raise $6 million.

Westerners not only donated money and time, but they also offered refugees jobs and even a place in their home. Catholic churches especially rallied for donations and any help the congregation could offer. Families stepped up to offer their homes to the unaccompanied children, like my grandfather who was just sixteen when he fled.

The UNHCR, established in 1950 after WWII, was originally a temporary agency. Though its High Commissioner had died months earlier in 1956 and they had not replaced his position, the remaining leadership managed the crisis effectively.

On November 4 alone, around 10,000 Hungarians fled as Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest. Many Freedom Fighters faced arrest, execution, or deportation, prompting mass escape efforts through forests, swamps, and snow, sometimes over hundreds of kilometers. Thousands of children, some alone, also fled.

Some refugees walked up to 500 kilometers from the eastern side of Hungary towards the west. Parents told their young children to escape to save themselves, believing that sending their children across the border alone was safer than living under the Soviets.

Though Soviets soon tightened border controls, nearly 194,000 Hungarians escaped within months—about 174,000 to Austria and nearly 20,000 to Yugoslavia. Most wanted to head west, away from Soviet control. By August 1957, nearly 80% had been resettled, with only 4% forcibly repatriated. Austria agreed to some repatriation under Soviet promises of safety, but many refugees distrusted those assurances.

After the refugees began fleeing in droves on November 4, European countries acted swiftly to help.

The French Red Cross sent a plane full of supplies to Vienna to help the refugees on November 7, and on the return flight to France they took a handful of refugees back.

On November 8, 400 refugees were sent to Switzerland on a train. Also on that day, President Eisenhower of the United States granted 5,000 visas for Hungarians to immigrate to America.

By November 9, several hundred refugees had been transported to France, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Sweden. The Swedes began resettling Hungarians immediately after the revolution began in October while Swedish politicians advocated for other countries to do the same.

Nine European countries had taken in 21,669 refugees by the end of November. By the end of December that rose to 92,950 refugees and 37 countries. After arriving in Austria, refugees were sometimes resettled in another country within 48 hours.

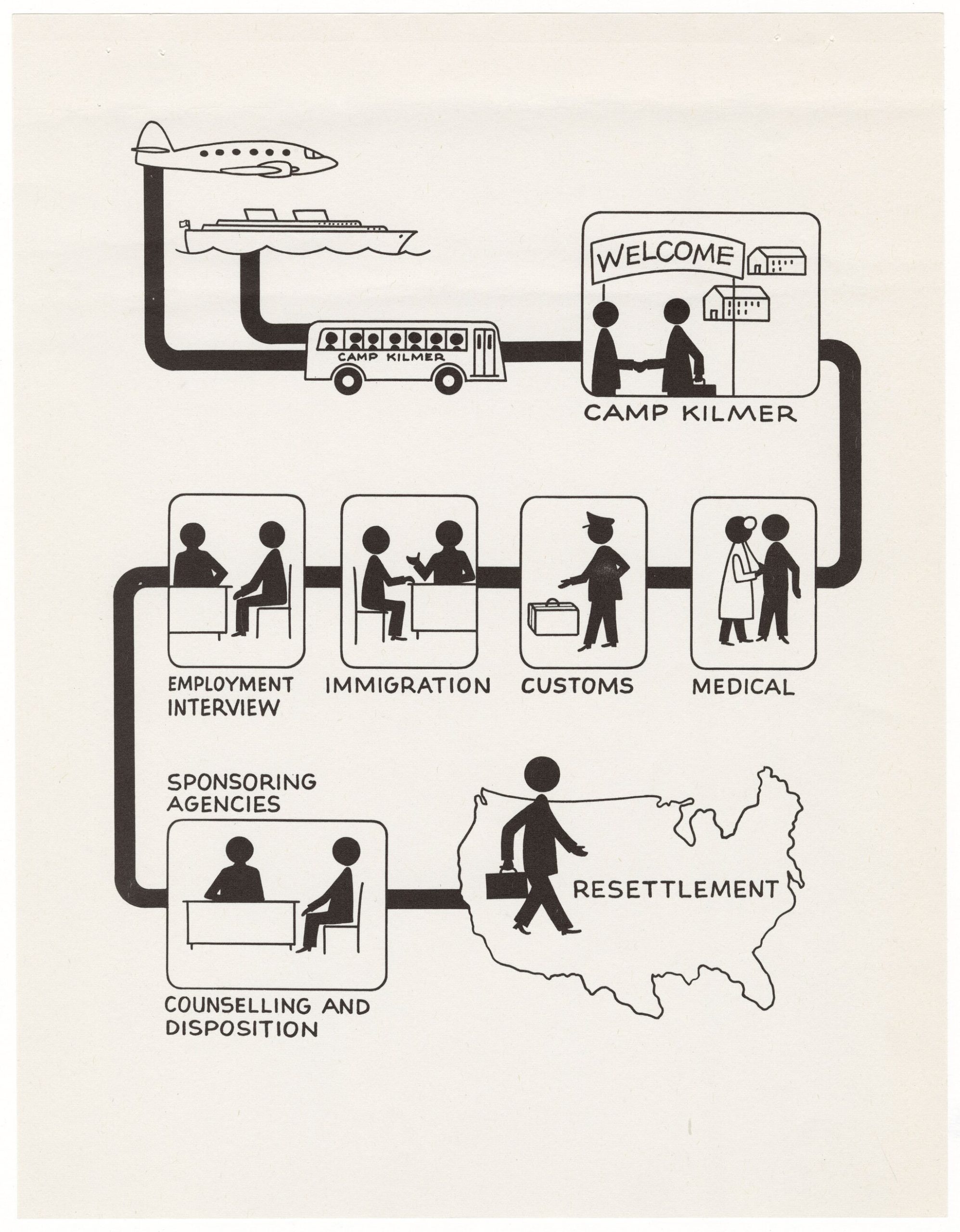

A poster outlining the process for accepting Hungarian refugees in 1956,

by the Department of State, International Cooperation Administration.

The U.S. admitted over 33,000 Hungarians through Operation Safe Haven in just nine months. Operation Safe Haven involved relocating thousands with the help of military bases, naval ships, and plane transports.

There were contradictory opinions in America about letting Hungarians in, and politicians wavered. On the one hand, some Americans wanted to help the Hungarians underdogs who fled from the Soviets—which would also be good anti-communist propaganda for America. On the other, some people feared that the Hungarians could be communists in disguise trying to infiltrate America.

Refugees were processed at Camp Kilmer in New Jersey, once used as a staging area for World War II. The immigration process could be done in as little as an hour for each refugee. There were many volunteers that helped process paperwork, arrange transportation, and help place refugees with employers or sponsor families.

Most of the refugees were young, educated urbanites who longed for freedom and opportunities not available to them under Soviet control. Americans, although typically wary of refugees, welcomed the Hungarians with open arms.

Almost 194,000 refugees fled Hungary, and about half were resettled within two months. No other refugee crisis of that magnitude has been managed as quickly, and it likely never will be. Keeping up the momentum to handle immigration events like this is impossible, and the world has become more apathetic to the plight of refugees.

The anti-immigrant rhetoric and treatment of refugees and immigrants in America is deeply ironic and unsettling.

In the 1950s, bringing Hungarian immigrants to the US served a humanitarian and political purpose during the Cold War. Although Eastern European, Hungarians were largely white, and they were perceived as ideological allies instead of threats. They were freedom fighters, but other legitimate freedom fighters—especially from Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa—are portrayed as criminals.

Today, brown, black, and Muslim refugees often face the most discrimination, bureaucratic bottlenecks, detention, and societal ostracization. The shift in how Americans treat immigrants highlights that race and religion play a large role in determining who receives help and sympathy, and that geopolitical moves influence humanitarian decisions like helping refugees.

Currently, the approach to combat immigration in the US is to expand detention centers, dismantle asylum protections, aggressively seek and deport people—including to third-countries that they have not been to—and to eliminate longstanding relief programs. These policies hinder people’s right to due process and pave the way towards extreme authoritarianism.

Also ironic is Hungary’s treatment of brown and Muslim refugees and their anti-immigrant rhetoric mirrors that of the United States. Refugees from Africa and the Middle East have been severely mistreated in Hungary, in similar ways as Latin American immigrants are treated in the US. Not only that, but Hungary’s Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, announced earlier this year that Hungary plans to withdraw from the International Criminal Court so they cannot be bound by the ICC’s rules. This reflects a troubling disregard for human rights and international law.